On Saturday, 25 April 2015, a 7.6 magnitude earthquake occurred in Gorkha district, approximately 76 km northwest of Kathmandu. There were more than 9,000 estimated casualties and approximately 23,000 injuries. 31 of the country’s 75 districts were affected, with 14 severely affected. More than half a million structures were damaged or destroyed, displacing hundreds of thousands of families.[1]

The National Reconstruction Authority (NRA), established in December 2015, is the legally mandated agency for leading and managing the earthquake recovery and reconstruction in Nepal.[2] The agency was established with the explicit goal “to promptly complete the reconstruction works of the structures damaged by the devastating earthquake of 25 April 2015 and subsequent aftershocks, in a sustainable, resilient and planned manner, to promote national interest and provide social justice by making resettlement and translocation of the persons and families displaced by the earthquake.”[3] The Post Disaster Reconstruction Framework (PDRF) is the institutional mechanism through with the NRA facilitates and oversees reconstruction, using an owner-driven reconstruction model which has been used in contexts such as Gujarat, India after the 2001 earthquake, and in Pakistan after the 2005 earthquake.

Owner-driven reconstruction (ODR) models center homeowners in the re-building process by giving reconstruction aid directly to owners vs contracting with intermediaries in the private sector to rebuild homes.[4] Most ODR mechanisms rely on multi-disbursement financing - where the government funds/grants are provided to residents in staggered installments - to ensure code compliant reconstruction in each phase, reducing vulnerability to future earthquakes. In theory, ODR models can also minimize displacement by allowing homeowners to rebuild on the sites of their existing homes.[5]

Despite the potential benefits of owner-driven programs, the reconstruction program in Nepal faces many challenges. As of August 2017, thousands of affected households remain homeless and unable to rebuild. Of the 767,705 households initially eligible for the program[6] only 122,309 households have received their second installment, and an even smaller 32,801 beneficiaries have received their 3rd installment.[7] Inability to receive the second and third installments results from a failure to comply with the NRA’s earthquake resistant reconstruction guidelines.[8]

Based on research, in depth interviews, and site visits conducted in January 2017 and August 2017, the most common barriers preventing households in the Kathmandu Valley from rebuilding are land registration and documentation, lack of adequate financing, and strict building bylaws and design requirements. Thus, while owner-driven models can contribute to homeowner empowerment by involving them in the project of rebuilding, the experience in Nepal shows how, without the right systems in place to support vulnerable populations through the reconstruction process situations of protracted displacement can take hold.

Land Registration and Documentation

The first barrier is a lack of formal documentation of land title, one important feature of tenure insecurity. While households may have been living without documentation for generations, the earthquake brought challenges of land registration to the forefront. As a result, those households which have been identified as squatters, or those living on government-owned land, are often restricted from the program even if their homes were fully destroyed because they were unable to provide documentation of land ownership. The fact that beneficiary identification cards are issued at a local level by municipal officials or other local committees has benefits and drawbacks: local decision-making means that ownership can sometimes be determined through local knowledge; however, the process is also vulnerable to political patronage and corruption. To complicate things further, even if a household is provided a beneficiary card from local authorities, municipalities will not approve reconstruction designs or release funding until land registration has been finalized. Land registration through the central government constitutes a major barrier for many households because formal land registration is an expensive process that requires retroactively paying taxes to the government since the last round of land registration in 1979. High costs and lengthy procedures make this process prohibitive for many families. The requirement to provide formal land registration also favors private land ownership, as landless people and those who live on communally-owned land are ineligible from participating in the NRA’s reconstruction program. This challenge can result in already vulnerable populations becoming additionally marginalized through the reconstruction process.[9]

Financial Constraints and Identity Verification

Beyond the challenges of landownership described above, financial constraints remain the primary barrier to reconstruction for most families. Many of the households most affected by the earthquake are also the most socially and economically vulnerable. The PDRF mechanism distributes funding to households by direct transfers into beneficiary bank accounts. Thus, those communities without a bank branch, as well as those households without a bank account, find it difficult, if not impossible, to access disbursements. In some cases, commercial banks will not release funds to beneficiaries due to discrepancies in beneficiary identification and bank account information.

Lack of documentation is not only an issue for opening bank accounts; approximately 20% of the population in Nepal does not possess a citizenship certificate, especially vulnerable low-caste and indigenous groups.[10] Many people also lost citizenship documents due to the 10 year conflict and recurring natural disasters. The process for obtaining a citizenship certificate is not straight-forward and many individuals do not know the procedures to apply. Additionally, the documents required to obtain a citizenship certificate are documents may often require a citizenship certificate to obtain (such as land title or voter registration)[11]. This cycle has isolated many vulnerable groups from the reconstruction process and their prospects for obtaining the necessary requirements. These challenges are exacerbated by weak administrative capacity to manage such issues[12]. While local verification can be done by local officials and community agreement, beneficiaries still must wait for verification and authorization at the national level, increasing wait times.

Even if beneficiaries are able to provide documentation to establish bank accounts, the funding provided by the NRA through the PDRF is not enough to completely rebuild even the most modest Nepalese home, especially in urban areas where construction and material costs are high. Thus, families must find additional funding sources to complete each phase of construction, often relying on private banks. Unfortunately, commercial banks have not been able to meet the demand, and many low-income households are ineligible for loans.

The financial challenges of reconstruction are immense. However, the experience in Nepal shows that financial institutions such as banks and ODR mechanisms are often inaccessible to the most vulnerable groups, due to lack of formal documentation and limited access to financial resources.

Building Bylaws and Design Requirements

The last major challenge is that reconstruction guidelines are too strict and prescriptive to adapt to the multiple needs and budgets of affected families. Despite the wide variety of housing typologies throughout Nepal, the NRA put forward a limited number of different earthquake-resilient design options that could receive ready approval from municipalities for funding disbursal[13]. While this effort may be well intentioned in terms of ensuring earthquake-resilient structures, the small number design proposals are not sufficient for meeting the housing needs of the many diverse communities in affected areas. To access funding for reconstruction, anything different than the designs provided in the reconstruction catalog requires approval from with NRA engineering staff. The money and time required to go through the elaborate process of developing detailed architectural and engineering drawings to fit each unique structural need is nearly impossible for most households.

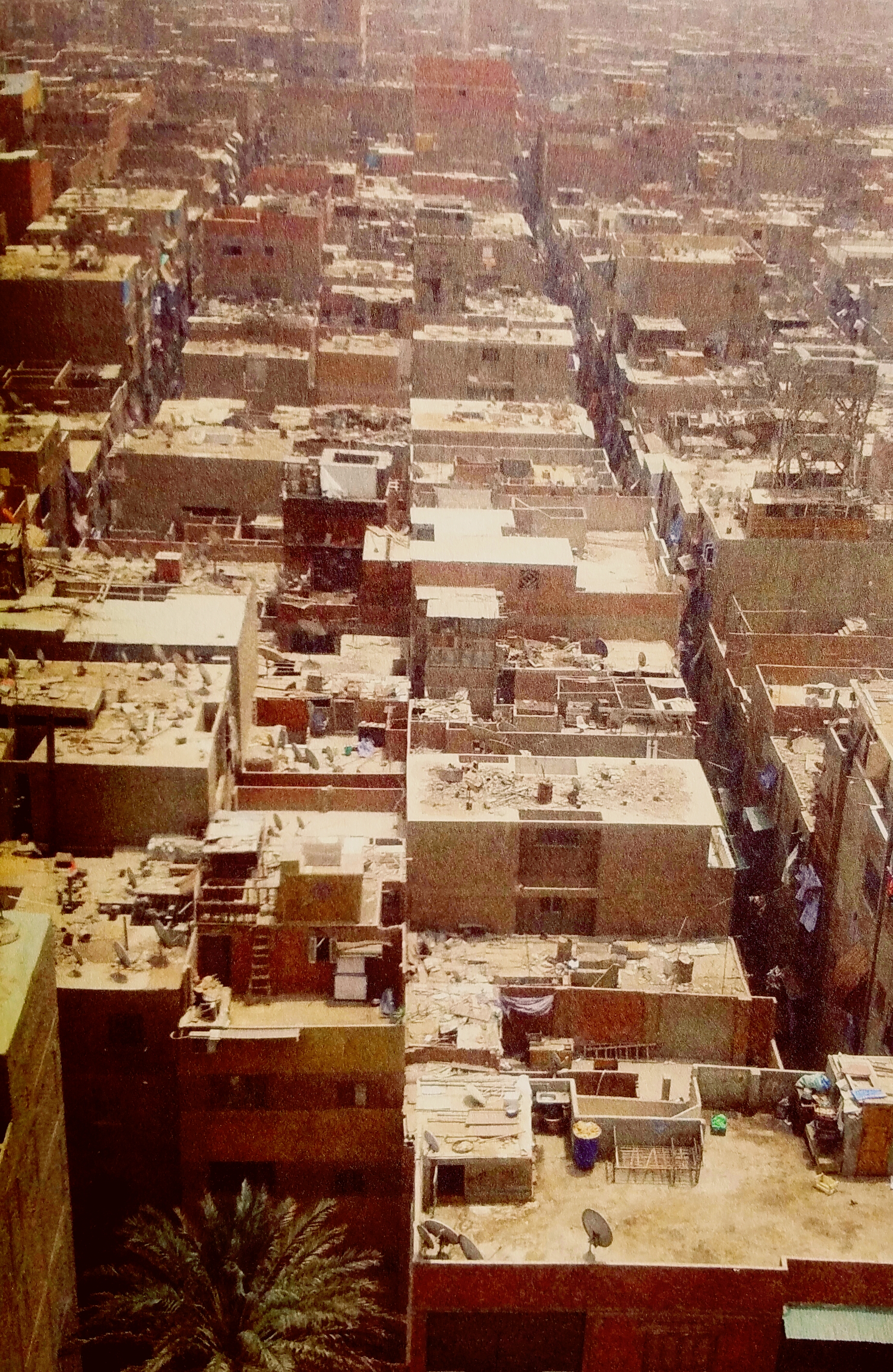

In particular, Newari communities in Nepal have faced challenges with rebuilding in their traditional homes, due to the high-density and narrow construction used in the urban and peri-urban agricultural settlements. While there are some examples[14] of communities who have been able to rebuild with engineering and design help from NGOs such as Lumanti, Support Group for Shelter, other communities facing similar structural requirements are not able to access such assistance to rebuild in a culturally appropriate way. Because cultural adequacy is an important component of the right to adequate shelter, this is cause for great concern.

Summary

A disaster of the magnitude of the 2015 earthquake will undoubtedly take many more years to recover from, but the PDRF itself faces many serious challenges which warrant reflection and action. Programmatic and administrative hurdles at multiple levels act as an unnecessary hindrance for rebuilding, resulting in two problems: first, many households are moving forward with unmonitored construction resulting in a lack of control over seismic resistant construction, potentially leading to future vulnerability to earthquakes. Secondly, there is an increase in inequity between those households who can afford to rebuild without NRA assistance and those who cannot, further marginalizing the poorest, who are often in the most precarious housing situations. Rather than punish families for failing to comply with difficult and expensive building guidelines, the NRA should prioritize the right to housing and help families overcome the hurdles of the existing reconstruction process.

Reconstruction after a disaster such as an earthquake is a daunting task, but it is within the responsibility of government to ensure that all households are able to equally access the resources needed to ensure the right to housing after such catastrophic events. Without proper procedures in place to minimize these hurdles, protracted displacement for the most vulnerable households will undoubtedly continue. One useful model for approaching a more effective reconstruction program is by supporting community-driven reconstruction programs, instead of owner-driven reconstruction programs alone. One important example of this is the work of Lumanti, Support Group for Shelter, which will be the second blog post in this series.

[1] World Bank, Nepal Earthquake Post Disaster Needs Assessment. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/546211467998818313/pdf/97501-WP-PUBLIC-Box391481B-nepal-post-disaster-needs-assement-report-PUBLIC.pdf

[2] “National Reconstruction Authority,” National Reconstruction Authority, accessed March 2, 2017, http://www.nra.gov.np/news/details//.

[3] Ibid.

[4] “Owner-Driven Housing Reconstruction Guidelines.” International Committee of the Red Cross, n.d.

[5] Tafti, Mojgan Taheri. “Limitations of the Owner-Driven Model in Post-Disaster Housing Reconstruction in Urban Settlements.” Department of Planning, University of Melbourne, n.d.

[6] It is important to note that this post focuses only on those families which were approved to participate in the reconstruction mechanism; thousands more families were deemed ineligible for the program for a variety of reasons, including political reasons such as discrimination and exclusion, lack of citizenship cards, or relative isolation.

[7] National Reconstruction Authority Website. Accessed 12/06/17. http://nra.gov.np/mapdistrict/datavisualization

[8] Gathered from interviews conducted by the author with municipal officials and NGO personnel. Nepal, August 2017.

[9] Oxfam. “Buiding Back Right Nepal: Ensuring Equality in Land Rights and Reconstruction in Nepal,” April 21, 2016.

[10] CARE Nepal, Community Self Reliance Center. “Housing, Land, and Property Issues in Nepal.” Care International, 2016. https://insights.careinternational.org.uk/media/k2/attachments/CARE_Housing-land-property-issues-in-Nepal_Feb-2016.pdf.

[11] Gathered from interviews conducted by the author with municipal officials and NGO personnel. Nepal, August 2017.

[12] Oxfam. “Buiding Back Right Nepal: Ensuring Equality in Land Rights and Reconstruction in Nepal,” April 21, 2016.

[13] “Design Catalogue for Reconstruction of Earthquake Resistant Homes.” Nepal Housing Reconstruction Program, Government of Nepal, Ministry of Urban Development, 2015.

[14] Gathered from interviews conducted by the author with municipal officials and NGO personnel. Nepal, August 2017.