The Durable slum: dharavi and the right to stay put in a globalizing mumbai

liza weinstein

(university of minnesota press, 2014)

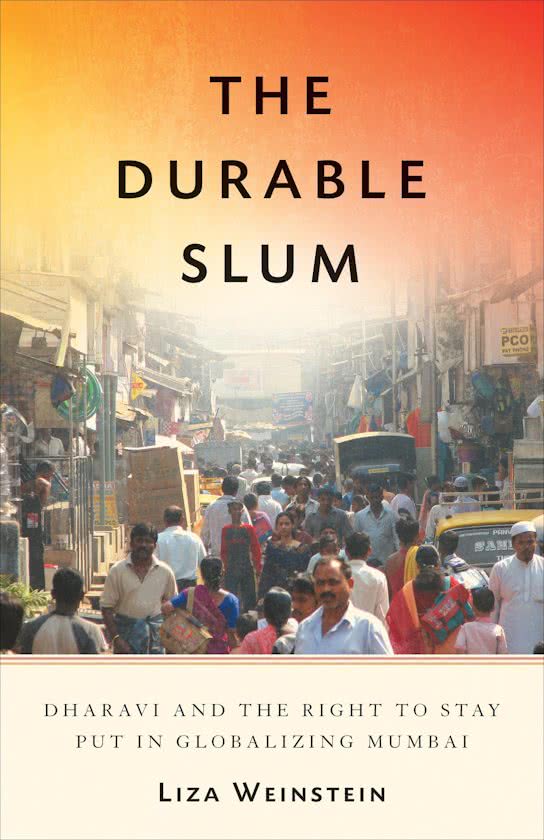

When mentions of informal settlements are made in the popular press and public debate, a particular image of the slum usually comes to mind. With its seemingly endless expanse of squat, aluminum-sided, blue tarp-roofed shanties, Mumbai’s iconic settlement of Dharavi – referred to both pejoratively and affectionately as “Asia’s Largest Slum” – fits this image better than most. Visible from flights into Mumbai’s international airport and from the windows of most taxi rides into the island city, nearly all visitors to Mumbai encounter Dharavi and its romantically bustling streets, which both confirm and defy their preconceptions of the slum.

Among the various tropes used to understand slums in general and Dharavi in particular are conflicting notions of permanence and precariousness. On one hand, places like Dharavi appear as intractable social problems and planning quandaries that have defied decades of attempted solutions. But on the other hand, they appear fragile in the face of powerful real estate interests and efforts to now make cities “slum-free” and “world class.” In the Durable Slum, I examine these tropes and the partial realities they reflect. I use the case of Dharavi and the string of efforts to “de-slumify” this space to examine the shifting landscapes of power, vulnerability, and displacement amid global urban development underway both in India and beyond.

More specifically, I venture an answer to the question of how Dharavi and its seemingly marginal residents have held on, for over a century, to some of the most valuable land in the city of Mumbai, and by extension, in the world. By situating, the Dharavi Redevelopment Project (DRP), the latest effort to redevelop Dharavi, in historical perspective, I find that while government officials and property developers may wish to bulldoze the settlement, their accumulationist aspirations face a powerful set of opponents. Dharavi’s durability, I find, is rooted in the centrality of the settlement within economic and political networks; Mumbai’s diverse and fragmented institutions of planning, governance, and politics; and local mobilizations around the right to stay put.

In particular, I use Chester Hartman’s classic notion of the “right to stay put” to frame the resistance that emerged to DRP between 2004 and 2010. While Hartman’s ethnographic site of 1970s San Francisco differs dramatically from Mumbai of the early 2000s, his understanding of staying put – not as a legal right, but a platform for political claims-making – resonates with the diverse demands being made in Dharavi at the time. Like many of the residents, workers, and activists resisting the DRP, Hartman argued “that government [should] plan housing and prevent displacement instead of simply compensating the victims after the fact...[and] make government policies responsive to existing residents, not to financial interests or the mobile gentry.[1]” In Dharavi in the early 2000s, this claim was made at the ballot box, in the courtroom, inside government planning agencies, and on the streets. In contrast to the more revolutionary framing of Henri Lefebvre’s “right to the city” or the urban social movements classically described by Manuel Castells, Hartman’s framing acknowledges that the threat of displacement can keep claims-making focused on a much narrower and more immediate set of objectives. Additionally, its more general focus on space can accommodate both urban and rural struggles against displacement within the same frame. This is particularly important in India, where movements against displacement frequently transcend spatial boundaries, as represented in developments along the urban fringe or in the anti-eviction activism of the National Alliance of People’s Movements, for example, which has resisted displacements caused by both rural river dam projects and urban slum demolitions.

Despite the way Dharavi often stands in for slums in general, it is important to recognize it as a distinctive space, both globally and within Mumbai. Its size and geographic centrality distinguish it from most of Mumbai’s other settlements, which tend to house a few dozen families along railway tracks or highways, and remain much more vulnerable to government bulldozers. While longstanding interests and entrenched political networks have protected Dharavi and its workers and residents, it is facing a new and more powerful set of opponents, backed by both global capital and national state power. And while Dharavi remains in place – at least for the moment – it is important to recognize that the residents of many other settlements are significantly more precarious.

Most importantly, the case of Dharavi demonstrates that struggles over the right to stay put, even when they succeed, can be as detrimental as they are empowering. While the political fragmentations, administrative weaknesses, and influence of local activists have erected useful barriers to potentially destructive development schemes like the DRP, they can also entrap residents. Without a viable alternative vision for Dharavi, the residents continue to live under conditions of precarious stability. Under this condition, the threats of dispossession remain, few investments are made, and residents wait for the project to be revived or replaced by an even grander scheme. And durability, as represented by the contradictory tropes of permanence and precariousness, endures.

[1] Quoted in Swanstrom and Kerstein 1989. "Job and Housing Displacement: A Review of Competing Policy Perspectives." In M.P. Smith (ed.) Pacific Rim Cities in the World Economy: Comparative Urban and Community Research. Transaction Publishers, pp. 254-296.

Liza Weinstein is an associate professor of sociology at Northeastern University. Her research and teaching interests focus on cities and globalization, urban political economy, the politics of informality, and state-civil society relations with a regional focus on India. She is the author of The Durable Slum: Dharavi and the Right to Stay Put in Globalizing Mumbai (University of Minnesota Press, 2014). Based on historical and ethnographic research in Mumbai’s infamous Dharavi settlement, the book examines the Indian state’s changing response to residential informality in the context of economic globalization and global city formation. Her current research is a comparative and historical study of residential evictions and housing rights activism in five Indian cities.